Finding balance in operational management can be challenging. In complex organizations, where teams juggle priorities across multiple departments and stakeholders, conflict is not just inevitable—it’s routine. A request from one unit might directly contradict another’s. A stakeholder may second-guess a decision after it’s been executed. Tensions rise. Emails fly. Meetings multiply. And often, the response is the same: change the process.

But should we?

There’s a subtle but important distinction between reacting and overreacting in operational management. Knowing where to draw the line can mean the difference between smart adaptability and process fatigue.

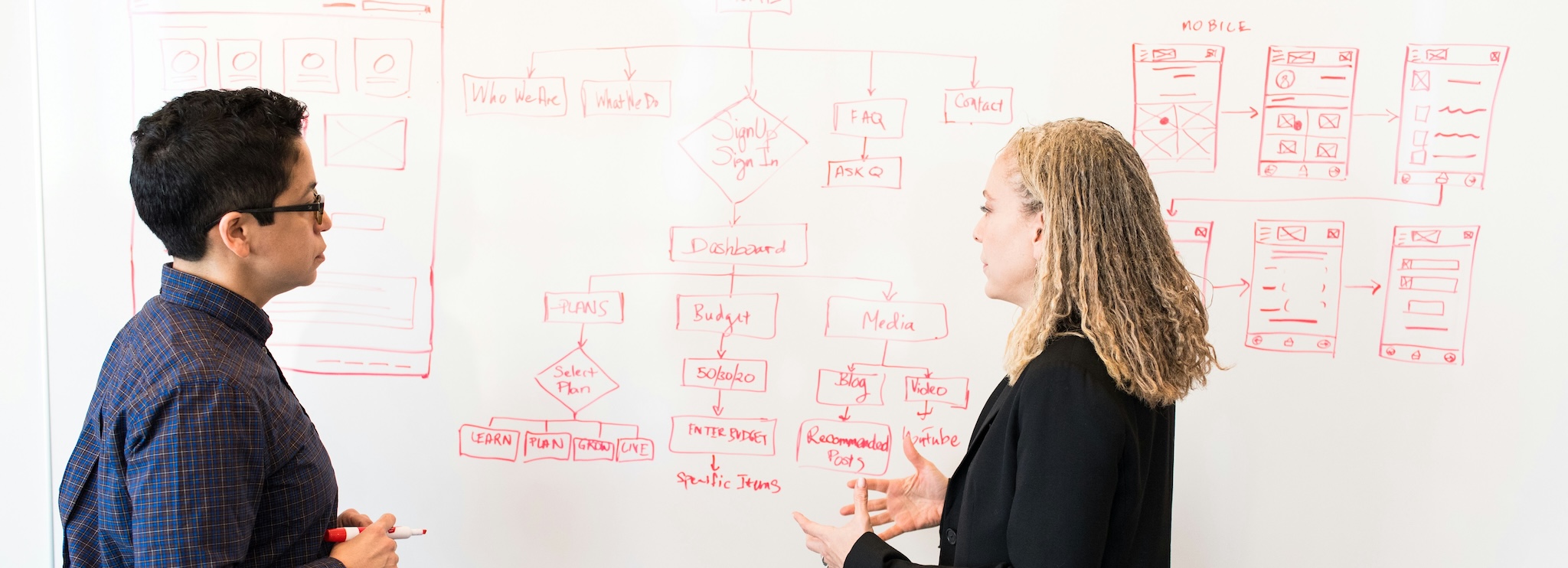

Photo by Christina @ wocintechchat.com on Unsplash

When a Reaction Is Warranted

Let’s be clear: some conflicts do reveal legitimate gaps in workflows. For example, if an approval step was missed that caused a project delay—or if two departments are consistently duplicating efforts—a revised process or added layer of review may be essential. In these cases, introducing new workflows or cross-functional approvals can reduce future friction and increase accountability.

Being responsive and iterative with your operational processes is a hallmark of good management. But it requires discernment.

When You’re Overreacting

Here’s the pitfall: the urge to solve every problem with a new policy, process, or approval can lead to bureaucratic overload. Sometimes a conflict isn’t systemic—it’s circumstantial. It may be the first time an issue has occurred in five years. Or it may be a rare miscommunication between two teams that usually work well together.

In these cases, altering the process may not improve outcomes. It may just slow everything down for the next five years in the name of solving a problem that only happened once.

This is where overreaction creeps in. It’s driven by a well-intentioned desire to mitigate risk and create order, but in practice it often complicates workflows, adds inefficiencies, and reduces trust in the process itself.

The Risk of Risk Aversion

Managers—especially functional, operational, and project leads—often feel pressure to demonstrate control by putting in safeguards. And yes, being proactive is critical. But so is accepting that not every bump in the road needs a detour sign and a traffic light.

It’s okay to accept that a process failed one time. That doesn’t mean the process is broken. It means you’re operating in a real-world environment with real people and real variability. Your goal is not perfection—it’s progress.

A Thoughtful Framework

When conflict arises, ask yourself:

- Is this a recurring issue, or a one-time event?

- Would changing the process prevent this from happening again—or just add friction for everyone else?

- Is the risk tolerable, or truly unacceptable?

- Are we trying to solve a people problem with a process solution?

These questions can help separate necessary reactions from overreactions. Not every conflict demands a structural fix. Sometimes, it just needs a conversation, a little grace, and a willingness to move on.

Final Thoughts

Operational leaders have a tough job. You’re the bridge between strategic intent and daily execution. But in trying to be responsive, don’t fall into the trap of over-correcting. Not every process needs to be optimized every time. Sometimes, the best action is knowing when not to take one.